The hardest thing in life to learn is which bridge to cross and which to burn.

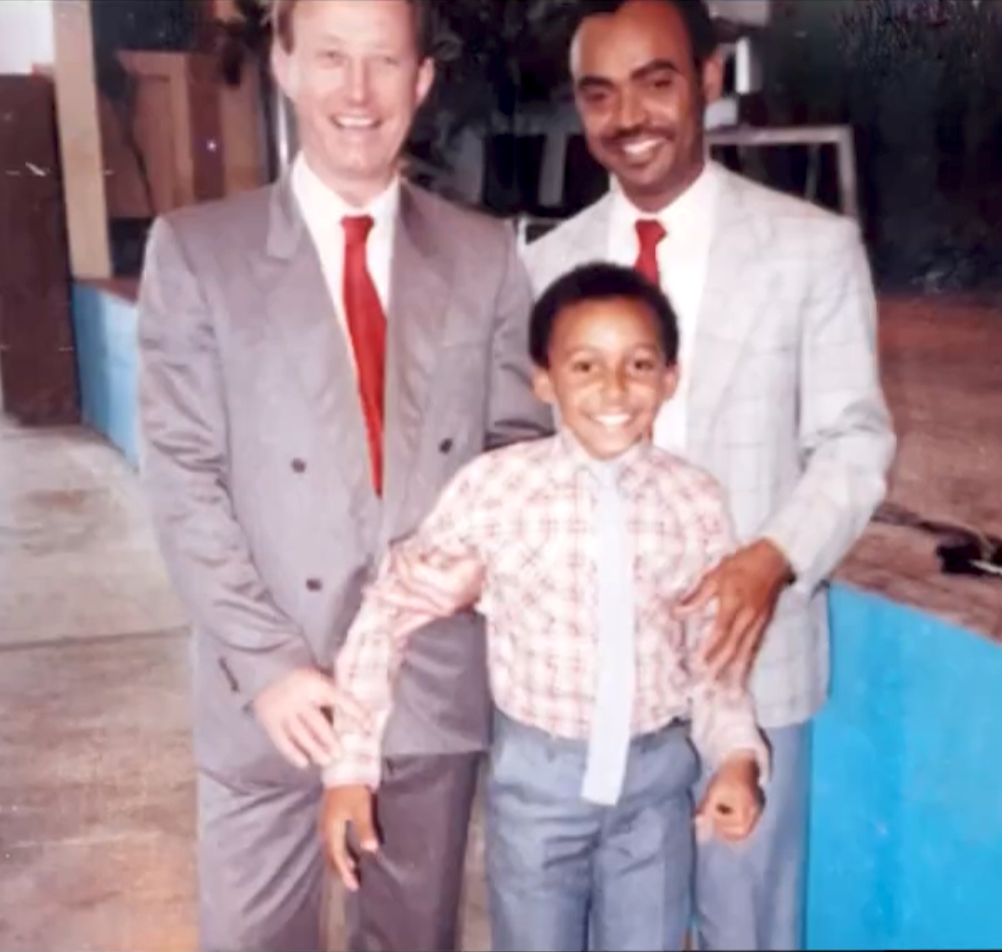

David Russell

The thing I remember most about leaving the Jehovah’s Witnesses was how much time it felt that I had.

By removing all of their events, readings and busy-ness from my schedule it was as if I had uncovered a whole other life. When my dad – Eddie Minnis – and my sisters Nicole and Shan say in the “Ting an’ Ting” documentary that they spend most of their time in the Witnessing work, they’re not joking. Being an active Jehovah’s Witness is like having a full-time job on top of your full-time job. And one where the boss expects you to put in more and more overtime.

With all of that time available to me I threw myself into my studies at the College of the Bahamas. This is the period I was referring to in the documentary when I said that I “locked myself in a room and just painted.” The room in question was the second floor of COB’s S-Block where I was doing an associate’s degree in Art with an unofficial minor in English with classmates and colleagues like Jace McKinney, Lavar Munroe and Jackson Petit.

I was twenty-five and I was a newborn. Everything was fresh, foreign and strange. I got to celebrate my birthday and Christmas for the first time. Went to Junkanoo. Dated non-Witness women. I joined Track Road Theatre where amongst other lessons I learned to curse.

What I was learning though were things that most people had learned when they were in their early teens or never had to learn at all.

Reminders of my past life still haunted me. Nassau is a small place and I kept running into former friends, or as I was trained to call them, “brothers”, who would no longer look me in the eye or speak to me. Each encounter was like sandpaper on my soul.

Not only was I now disfellowshipped but because I had stopped believing and could back up my non-belief, I had earned another label: “Apostate”. For Witnesses, apostates are described as stand-ins for the Devil himself. While they practice shunning of former members, they practically run away from apostates. It was like they all owed me money.

1.

When my doubts about Witness teachings really began to show, my family staged an intervention. My parents invited me to Eleuthera for a few days to talk about things. They did everything but burn sage in the house. They sympathized, shared some of their own nagging doubts. My father even said that he had come to similar conclusions as I had about certain Witness doctrines.

They sent me to visit a family friend in Rock Sound who was also an Elder. They hoped that maybe he could get through to me. After a day of trying he threw up his hands and said that this was my artistic nature coming out and there was nothing he could do.

At this point it was obvious that I wasn’t long for the faith. The Witnesses wouldn’t, couldn’t just let me be. The Elders would come as inevitably as the Terminators and I would be thrown out. This was when my sisters cried over me, when my family begged me to shut my mouth and just fade.

It felt like I was attending my own funeral.

The Witnesses wouldn’t, couldn’t just let me be. The Elders would come as inevitably as the Terminators and I would be thrown out.

As expected and as the Watchtower instructed, once the inevitable announcement came for me, it was as if I was suddenly dead to them.

My sisters have seen me walking on the road in Nassau and pressed gas.

My parents stopped supporting me through my studies at COB and left my maternal Aunt and Uncle to pick up that financial slack.

None of them came to see my play “The Cabinet” when it was on at the Dundas or the old Shirley Street Theatre.

None of them came to my wedding.

None of them visited when any of my three children were born.

2.

While my sisters have essentially cut me off, to say that my parents don’t talk to me is not entirely true. It’s a bit more complicated than that.

What communication we do have is strained. For example, I call my parents every year on their wedding anniversary, it’s one of the few things Witnesses are allowed to commemorate, and sometimes that has been our only contact for the year. If there is a life event, like an accident or a hospital visit, I get a call from them to let me know about it. If I start calling too frequently then I am told to stop.

When we do talk, the conversation is cordial, as if there is nothing wrong – as long as we stick to generalities and avoid any touchy subjects.

My three children – their only grandchildren – are a bone of contention. My parents have told me that the reason they don’t have a relationship with them is because of me. Apparently I need to let them all interact without my apostate self getting in the way. In other words, I need to give them my kids then leave the room.

Now, I know the Witness playbook too well to fall for that one. I don’t want my kids to get even a whiff of indoctrination so my response to that suggestion has always been a definitive “hell, no.”

A few years ago my mother accepted my terms and started calling the kids with me in earshot. While my father hardly ever joined in, she called about every week for almost a year and then just suddenly stopped. We later learned that since I was involved, even in such a limited role, Witness guilt had gotten the better of her. She didn’t feel that she was being faithful to Jehovah.

3.

In August of 2024 I brought my tribe with me to visit Nassau and Eleuthera. I wanted my then nine and six year old girls to get a chance to see their roots since they were now old enough to remember things. I was beyond shocked when my parents – and my sisters – said that they wanted to meet us. I was even more surprised when they showed up in broad daylight and came inside.

These were all unprecedented actions. For Nicole that was the absolute first time that she had ever seen or talked to my wife or any of my children and for Shan it wasn’t that much better.

The whole thing was as awkward as you could imagine.

I asked them if there was some Witness rule change that would allow them to meet and visit with us and with me, an apostate. They didn’t answer. I pressed further and my father said that they had made an “exception”.

It took me a while but I now think I know what that “exception” was all about. There is this Witness bylaw that they call “Theocratic Warfare.” It allows them to lie, deceive and bend the rules just a bit, or even talk to an apostate, if doing so would make their religion look better to outsiders.

The business they were likely after was removing a title card from “Ting an’ Ting” that said my kids don’t know their aunts or grandparents. So having met my children, ever so briefly, the text was removed as being inaccurate and then things promptly went back to being the way they were before. Silence from the sisters and my father, and the every-so-often calls from my mother.

I was suckered.

While the few “exceptions” exhaust and annoy me, they do seem to confuse my extended non-Witness family. Mission accomplished, I guess.

It’s led some of them to believe that maybe the thing blocking a reunion with my parents and sisters is me. While this might be true now, this was not always the case. I had long hoped that my family would find in themselves the power to break free from the Watchtower’s grasp and join me on the outside.

This hope also goes in the other direction. In the Director’s Cut my sister Shan says that “the door is not shut [for me].” She continued, “Where there is life there is always hope and we’re always hoping for the best.” The “best” that she is referring to, and the only way that I can be a part of the family again, is for me to repent for the crime of having thoughts of my own and return to the Witnesses.

For over two decades then my family and I have stood on opposite sides of a ravine. Each side hoping for the other to switch.

I now believe that our separate and opposite hopes are delusional.

It’s time we all moved on.

Facebook conversation on this post

Coming up next: "House Arrest and Daydreams" — I count the hidden cost of life under Jehovah’s Witness authority... and the price my family continues to pay.