I know them long time, them people is mine.

The women they’re fine, as long as you stay in line.

Ronnie Butler

If there wasn’t already a thing called reverse nepotism, then I would just have to invent it.

Family should beget favour, but in my case I get passed over for things that I actually qualify for. From a Jehovah’s Witness point-of-view, as a disfellowshipped former member and apostate, my family are commanded to shun me and so I must be excluded from their projects. The “Ting an’ Ting” documentary is the odd and singular exception where I want to be removed from something of theirs and they have decided to keep me in — but to keep me they had to cut out everything I said that went against their views.

When they have their family art shows, I am not invited to participate and I’m not there at the openings. I only exist as a loose thread on my father’s bio — that he has three children. I don’t even live in the country anymore, so ‘out of sight, out of mind’. The compound effect of these absences has led to the very common reaction — “I didn’t know that Eddie Minnis had a son”.

1.

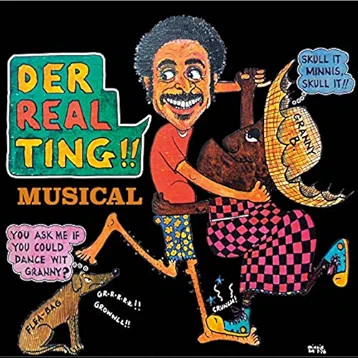

The “Ting an’ Ting” documentary has a number of great examples of this “reverse nepotism” in action. One of which is “Der Real Ting,” a juke-box musical written by Nicolette Bethel and Patrice Francis, directed by Philip Burrows that premiered in 2018.

Now, I talked to my father about doing a play from his music while I was in grad school — in 2009. I even wrote my own treatment for this “Eddie Minnis Musical” in that year while I was working on my own play, “The Cabinet.”

I’m not trying to say that I’m some genius for having the thought, because let’s be honest, stringing his songs into a narrative is not a radical idea – it was even done by the late great Eric Minns from a far smaller catalogue of songs in 2015 with his “Island Boy” musical.

At one point my father brought up the musical’s rehearsal process to me. He had observed that a lot of the children of people who worked on his music in the 70s and 80s were involved in the making of this production. I could only roll my eyes and suck my teeth.

That I, his son, was a playwright who brought him the idea nearly a decade prior and was now cut out from the entire process never occurred to him as odd or as the knife in my ribs that I took it to be.

2.

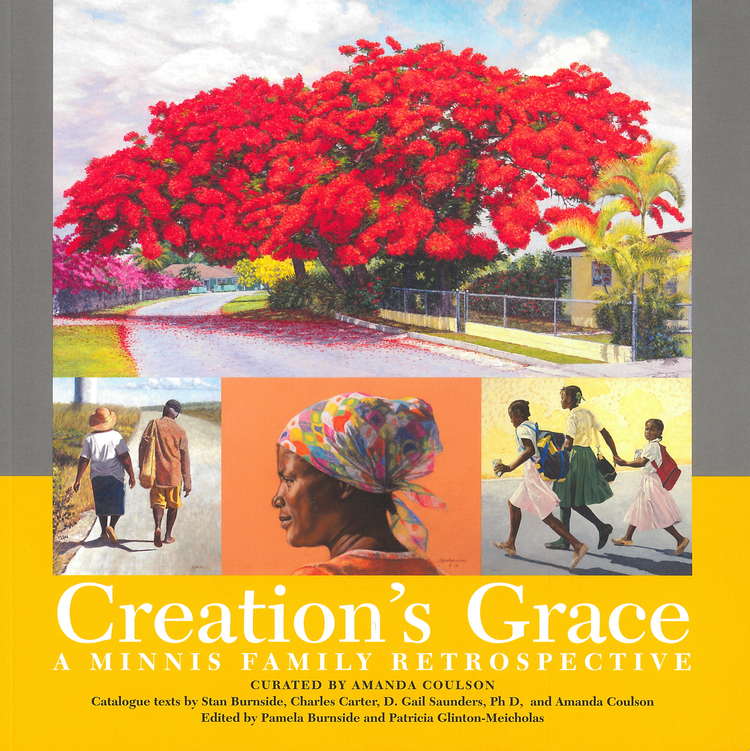

At first glance the “Creations Grace” Minnis Family Retrospective, also featured in the documentary, and put on by the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas (NAGB) in 2014 seems like more of the same reverse nepotism.

For one thing, it looked a lot like any of the shows that my family has put on recently, with the only difference being that it focused on past work instead of recent work. If you squinted, you noticed that there was also a son represented, but it was the son-in-law, Ritchie Eyma – who is an exemplary Jehovah’s Witness – and not me.

Despite all these similarities to what happened before though, you will see that this retrospective was quite a different beast. For one thing it was put on by the NAGB — a national institution — not a Witness affiliate by any means. The idea of the show came from the great Stan Burnside, one of the seminal Bahamian artists who was chairman of the board at the time. He passed this mandate to Amanda Coulson, Bahamian art historian and critic with international reach who had recently returned home to take on the NAGB’s Director job. She then gave the assignment to chief curator, John Cox, another major Bahamian artist and my art professor while I was at COB.

If you look up and down the list of people involved in the project or at least those who got their name attached to the catalogue — the late greats Patty Glinton-Meicholas and Dr. Gail Saunders alongside cultural hero Pam Burnside — there is not a Jehovah’s Witness to be found, and yet the final product looks exactly as it would if it were put on by the Watchtower society itself.

Since a retrospective is “an exhibition … showing the development of the work of a particular artist over a period of time” you would expect an Eddie Minnis retrospective to showcase his visual art work through time – and even to have some examples of his cartooning and maybe even his musical practice. And this was the original idea that Stan Burnside had.

This concept was expanded upon by Coulson as we read in Burnside’s introduction:

In her wisdom she [Amanda Coulson] expanded the original idea of an Eddie Minnis retrospective to include his family members.

This is where expectations shift.

If the show became a family retrospective then wouldn’t you naturally expect that all of the family that are artists would be represented? And would that not also include me? You might say though that perhaps the powers at the NAGB did not consider me to be an artist and thought that I should not be included because of that. Well let’s continue Burnside’s quote:

[The retrospective] is certainly an incredible showcase of what is now a “Dynasty of Minnis” artists, which also includes the Minnis’ son, Ward.

This was my first of two mentions in the catalogue. The second is found in my father’s biography as penned by Coulson:

Eddie and Sherry have three children; daughters Nicole and Roshanne and a son Ward (who is also an artist and a writer).

Here we have both the chairman of the board of The Bahamian National Art Gallery and the professional curator of the exhibit and gallery Director, both aware of my existence and acknowledging that I’m also an artist.

But the plot thickens. The NAGB was not only aware of me and my art, at the time they owned three of my paintings! Most recently they brought some of them out of the National collection to display in 2023 and 2024 in an exhibition entitled “The Nation / The Imaginary”.

What’s even wilder, is that when it comes to Minnis family art, they ONLY own my pieces and some from my father. Yes, you heard that right. Neither of my sisters nor Ritchie have any work in the NAGB’s National Collection.

If that’s the case – how is it that mention of me does not appear anywhere else in “Creations Grace”? How is it that not a single canvas of mine, even the ones that the NAGB owned, didn’t make it through to the Gallery floor for the family retrospective? How is it possible that there is no mention of my other artistic output: my poems, my theatre work, my cultural criticism?

If, in her wisdom, Coulson expanded the scope of the exhibit to include my sisters and then even further to include my brother-in-law, what wisdom prevented her from adding me to that list? And further still, why is this decision not explained anywhere?

It boggles the mind to imagine that a national institution curated a show of this magnitude along religious grounds as if they were a branch office of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The evidence that we have though, is the finished product, which surely looks and quacks like a religious hit job.

What followed after the exhibition was a decade of silence — a quiet cover-up built on the hope that no one would notice, and that even if someone did, they wouldn’t say anything.

And guess what?

It worked.

Coming up next: “The Art of Erasure.” A conversation long overdue — and that no one wanted to have — about the NAGB, the Minnis story, and what went missing.

Leave a Reply