Every body does like look at they shit.

I don’t know why.

I figure we does be admiring it.

Turn round and stare

watch it go down.

Put it on your resume.

Look what good work I do.

I got my shit together.

We does think our shit is best.

Only we can’t never smell it

we does be too close.

When I was young

used to call Mummy,

“come Mummy look come see,

I bumpee strong

like lion!”

Sooner or later you find out

no one into your shit but you.

That’s when you grow up.

Tag: seven skeletons

-

Meditation on Shit

-

Pedestrian Crossing

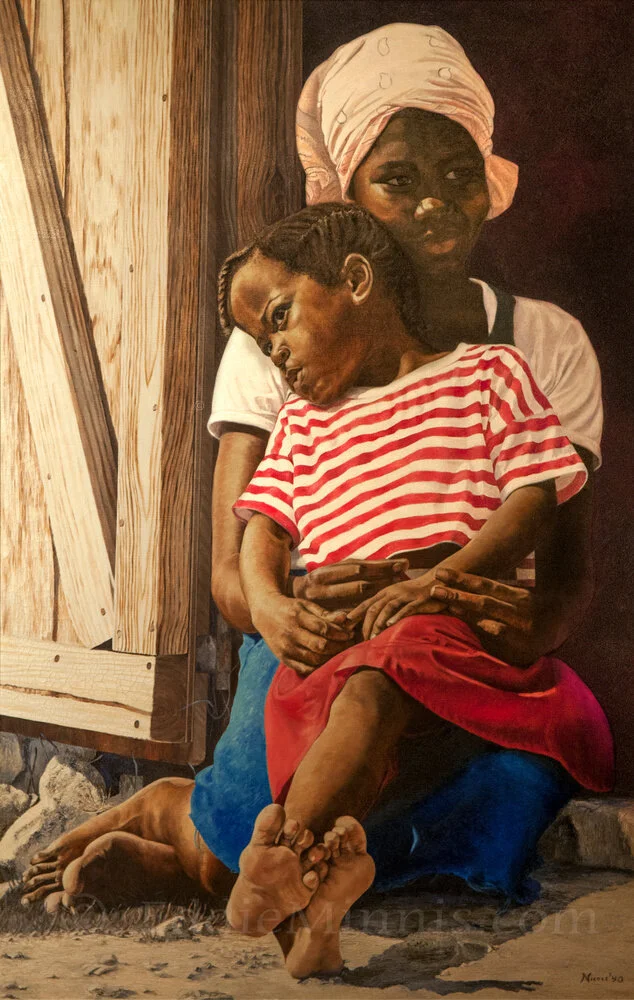

Pedestrian Crossing. 2003. Acrylic on Canvas. -

Upcoming Interview by ExJW Analyzer

I had the privilege to be interviewed recently by a legend in the exJW space – Jonathan Leger – for his YouTube channel.

The full interview premieres this Saturday at 7pm. You don’t want to miss it!

Here is a preview:

-

Support & Recovery Resources for Ex-JWs

Leaving — or even questioning — the Jehovah’s Witnesses can feel isolating. To make that journey easier, I’ve put together a curated list of books, documentaries, support groups, and creators who help explain the reality behind the organization and offer tools for healing.

Whether you’re recovering yourself, supporting someone who is, trying to understand what this religion actually asks of its members, or simply hoping to better understand a loved one’s journey, these curated resources offer guidance, education, and community.

You’re not alone, and you’re not without help:

-

Final Confession

For John Unrau

in memory of Erici.

You have become a black skeleton with flesh,

a burnt out stick of coal

in a diaper. The scent of urine mingles with death’s potpourri

for you have wet yourself yet again.

Where did your substance go? Burned off from hours of chemo

no doubt, the vibrant skin that once held life is now folded,

like your body, mirroring your worried brow

Huddled in the corner of a cot, in fetal position,

you have your back to me.

Do you even know that I am here? Do you care?

Nurse Rosie comes in with your evening dose of pills

carrying a transparent checker board calendar case

with your daily regiment

and a glass of water. Very hard to swallow

seeing you like this; like blood you have stuck to me in my trials

now I know that I will bury you.

Nurse touches your shoulder and you turn

“Richard time for your medicine.”

There is still motion in those bones;

much less flesh for them to carry now.

But your soul is heavy.

Dark clouds are poised over your head. Acid rain

has poisoned your eyes so that now they sit in your head

like hardened sapodilla seeds, dry, brittle and waiting to crack.

Total silence is your policy.

I’ve been coming here for weeks waiting for a word

to fall from your lips like a stone

that I could catch with my two hands

and polish into a paper weight.

But you never even look at me.

You take the pills one by one,

your throat agitates the water,

and I imagine they go somewhere.

There is no stomach that I can see,

perhaps it just passes through to the pampers

and gives the nurse something to do.ii.

Remember when we said that death was nothing to fear?

We were the brave fishers of men,

you the rusty headed sailor

and I, the new sparkplug,

your protégé. We speaking in tongues and raising the sick

pounding our bibles like we did the pavement,

wearing out our shoes

and the heathen’s ear in the same breath.

We were the missionaries

wearing our privilege as proud as any company man could.

Our policy was spoken in durable terms, an indelible contract

written in our own blood, so strong was our faith!

We believed.

We moved mountains for breakfast with our grits and butter

and daily peered into paradise

picking out lots for future possession.

We smiled when deprived for we knew

that the master above saw and would reward.

Counting the hours of the day when we spoke His name

like holy accountants,

for we knew God’s truth better than Moses ever did

and fire filled our bones with zeal for the master’s house.

Death was a joke for us;

we who stored our treasures in heaven,

and any who thought different were of a lesser calling,

they were made of lesser stuff.

Lesser than we who put our own flesh on the alter

to show we meant business.

Now.

Now that Death sits in the chair

in the corner reading the Thursday paper.

Now that his presence fills my lungs like napalm

and my skin burns at his every breath

I find that I can not say those magic words.

All of the books and talismans have turned to wax

and have lost their power

All of the advice of the prophets that I parroted so eagerly

now feels as hollow in my mind as a wind chime

knocking about in the smoke of a funeral pyre.

My God, My God, why have you bamboozled me?iii.

There is a knock at the door, and a head peers in

through the crack,

your ‘fleshly’ sister, and double in the faith,

herself veteran of many a crusade

she who tag teams with Rosie,

taking turns to wipe you clean of pride

“Rick, Brother and Sister Jacobs want to see you…”

You barely look, but the almost audible sound of your suck-teeth

communicates a profound disgust.

The head disappears again,

and we can hear the muffled excuses being offered

like candy to calm down kids.

Treat them kindly for they have position.

They were once your good friends

and they have traveled far to pay last respects.

But they are married, and thus, are the enemy.

You only allow your single friends,

admittedly not many now,

the pleasure of seeing you die.

I hear you suck your teeth again.

Perhaps it’s nothing against them personally

but perhaps it is the thought of what might have been.

I think of all the women, good church sisters all,

who wanted you

who would give the world now just to clean up your vomit

who would have wallowed in your urine

to sleep on the floor by your bedside,

just to have felt what it was to know a man.

But you were too righteous for such things.

Paul and the ever-virgin Jesus were your models.

You told me so many stories about sisters

who would send you messages

encoded in body language, asking strange favors

just to linger in your presence

to pass your way,

to catch your eye,

to get close enough for you to smell them

in the hope

that their perfume might awaken some forgotten instinct.

But women were only a distraction and temptation to sin,

so you stayed single,

married the Lord,

deadened your body members,

slept alone

and I, seeing you as a modern day messiah,

tried to follow.

But I was always weaker.

I still looked with lust. Trembled at night with desire.

I grew to fear talking to beautiful women

lest I snap under the strain.

The church, for its part,

lovingly closed off all options for release.

Masturbation was sin.

A first step in the wrong direction.

So I prayed for forgiveness from wet dreams,

every erection became a trial

and a sign that I had failed in my training.

Private thought was sin.

I daily scrubbed the lewd graffiti

off of the walls of my mind

that multiplied even as I cleaned,

even as I killed every flirtation,

every desire,

I was losing the battle.

Guilt was tattooed on my genitals,

and I hated my imperfection.

You made being a eunuch look so easy.

And now after all these years

to find out your secret wish.

You, who I thought had exorcised the demon of desire,

wanted a woman, a wife, maybe even child.

You sigh deeply,

your head still turned to the wall,

covered in shadow.iv.

This disease travels like a snake in your family tree.

Not so long ago you were the caretaker,

the hero who never needed help

never stopping for air.

Not so long ago it was your father.

Since you had never left home,

you were the first choice for his nurse.

And you wanted the job.

Not long before that it was your mother,

and you took care of her too

How much should one man take on alone?

You became legend.

The faithful would call your name in wonder.

Before sunrise you made your fathers breakfast

and changed his diaper

then went out into the mission to help the heathens see Christ

all before you went to your office job by nine, always on time.

Lunch hour would find you giving Dad a fresh wipe and diaper,

and cleaning up whatever was spilled on the floor and feeding him

before you were back talking to angry customers till five

then into the field you went again with joy,

for the harvest was great,

nightfall would find singing

while you rubbed your father's skin in oil

probably after you preached your prescribed sermon

and cared for the congregation

just as the rule book said that you should.

When did you sleep?

After years when he finally died

and you said the prayer at the graveside

you couldn’t cry.

You still stayed in the same house, entertained their ghosts,

and spent even more time proselytizing than before

And you took me in, I, a child who had left my parents

in search of the Lord, in search of understanding,

you gave me a home.

I wanted to be your clone,

to pour out my soul like wine for the faith and the flock, as you did

Now I sit with my head in my hands

impotent,

watching your last days slowly evaporate.v.

Six months before they found the Trojan in your blood

You came to me with news. You were going to live differently.

You were moving.

Your boss asked if you wanted to manage a small out island office

and you were going to take the chance.

They could have sworn you would say no.

There was a church on the little island that would be so happy

for your expertise. Definitely not your main reason.

But all your life you had lived in the same house,

the same Nassau neighborhood,

forty-four years of tradition and memories

in that one place.

Of course that meant that you were leaving me,

but at least I could still call.

I could not comprehend the seismic move.

Why now? What had changed?

“I tired ah living my life for other people.

“This my time now.”

Now, of course,

this isn’t how you planned it.

This not-so-triumphant return to the same house,

the same Nassau neighborhood

keeping the family tradition

and way of dying

It is hard to take comfort

in those six months of independence

six months that should have started

twenty-five years sooner.vi.

You tire of the wall and turn over,

in that moment I look into your eyes, and I try to smile.

I have nothing to say.

Neither do you.

But I see it.

Your eyes are like hollow wells that descend deep

into the abyss of your soul,

wells that haven’t seen water for so long that

vinegar beads up on their walls like sweat.

The spin doctors will sell your death to the faithful as a victory

they will say you received the reward of certainty into your palm

that you died and opened your eyes in paradise

joyous, having lived the life the way it must be lived.

But in your eyes I see the hell of their lies.

All of this time you spent feeding the sick and preaching the word

you did not want to see your own great hunger,

filling your belly instead with air cakes of doctrine,

filling your time with appointments,

chanting lines of salvation like code from a recipe book

but now the stench of foul gas cuts the tongue like a scythe.

The hunger is still there, but there is no more time.

And the hunger is for life.

To live.

To love.

To risk.

To find out now that the pearl of high price is made of plastic

is too much pain to bear.

You just close your eyes.

The half-smile on my face is frozen there.

I have just heard your confession,

I heard it in your eyes, as quiet as a thought,

and it has poisoned me. -

4: House Arrest and Daydreams

Tragedy is the difference between what is and what could have been.

Abba Eban

“God had to be first – no compromise, family had to be second.”

This is how my father describes his life’s priorities in the “Ting an’ Ting” documentary. Now, this is not an unusual stand in a religious society like the Bahamas, but what does it mean to be a Jehovah’s Witness with “no compromises”? When the main thing in your life is devotion to a cult what follows from that?

This is not the position of every Jehovah’s Witness, mind you. There are Witnesses who maintain relationships with disfellowshipped children and grandchildren. There are those who just live their lives; knock on some doors every other week and do just enough to maintain their standing. But these aren’t the role models, they aren’t the people who are celebrated at Witness conventions.

Witnesses can’t force all of their members to have the same level of fanaticism. Those that don’t display the right amount of zeal forfeit any hope of advancement. For example, you can’t be an Elder if your house isn’t kept in order. Until I “took a tangent,” to borrow his phrase, my father’s house was very much in order.

1.

To understand the Minnis family is to know that because they want to be good Jehovah’s Witnesses they have placed themselves under house arrest. It’s hard enough to be a regular cult member but to be a good one requires so much more.

This means that many of the decisions in their lives are made for them. From the very basic and trivial, like how they spend their time, to larger concerns, like whether or not to go to University, to have children or whether or not they can have a blood transfusion. You can see the impact of this core decision expressed over and over again in almost every aspect of their lives.

Because they want to be good Jehovah’s Witnesses they have placed themselves under house arrest.

Take higher education for example. When I finished high school in Eleuthera I didn’t even bother to apply to a college. I wanted to put Jehovah first just like everyone else before me had done and therefore didn’t see the point. I was going to be a “Pioneer” minister. I didn’t even know how I was going to make a living. Paint, I guess?

The Watchtower does not flat out say “Thou must not go to University.” What it does instead is call it a “personal decision” then not-so-gently tell you what to do anyway. Witness literature portrays Colleges and Universities as the home of Satanic philosophy. Since the end-of-all-things is so near, their argument goes, do you want to spend the short time left getting a degree in Satan’s home or earn God’s favour by knocking on doors? The “decision” is left up to the individual but if they want to be a good Witness the choice is clear.

If a Witness does decide to go, as I later did, they are judged for that choice and are labelled as not being ‘spiritual’ enough. While I was a member I couldn’t shake the guilt I felt for going to COB. Of course, my later turn away from the religion was chalked up as proof that Watchtower was right all along.

My sisters had the same mindset when they graduated high school. They both excelled academically, especially Shan, who got a remarkable eight A’s in her GCE O levels. Despite the obvious talent, they did not pursue any form of higher education. If memory serves, Shan actually applied and got accepted to numerous Universities, only to turn them all down.

The end of the world was apparently so near when they finished high school in the late 80s that there was no time to get degrees. They were applauded at the Kingdom Hall for making the best choice by giving Jehovah their youth.

Fast forward to now, nearly forty years later, the imminent nearness of Armageddon was still being used to scare others into the same dead-end choices up until very recently. On August 22nd the Witnesses suddenly reversed their decades long stance on ‘additional education’ – and have now made it ok for their members to pursue it if they so choose.

In making this radical U-turn, they didn’t apologize for their failed predictions or for the consequences their policies have had on millions of people. They won’t be made accountable for all the potential that they have wasted. In the end, it’s people like Nicole and Shan who are left holding the bag.

2.

Witness teachings like the Paradise Earth are deeply embedded in the family’s art. Paradise is the hope that the majority of members believe in and cling to; that after Armageddon they will get to live forever on Earth without sickness and death.

For example, when my father began his art practice, his landscape paintings would capture the complete view of a scene almost like an historian. However over time, as Amanda Coulson observes, he “began to deliberately excise objects of human intervention – cars, telephone poles, even the people themselves.”

This practice of removing traces of modern life from his paintings actually mirrors Witness images of paradise that also don’t include modern objects. Images in the Watchtower that do include things like telephone poles and street lights are horrific scenes from their imagined Armageddon.

“Objects of human intervention”, are therefore used as a kind of visual shorthand to show an image’s place in the Witness’ end-of-the-world timeline. Apparently, there will be no street lights in Paradise.

Lamp poles, street lights, high-rises, cars and other traces of modernity are mostly featured in Witness images of the apocalypse. Left image link to JW.org – Right image link to JW.org

Eddie Minnis as street historian with streetlights and lamp poles intact. On the left “Dean’s Lane” 1976. On the right “Mason’s Addition” 1990.

On the left “Gregory Town” by Eddie Minnis, 1992. In the middle, the same scene in 2025 via Google maps — while the scene has changed over the years, note the visible infrastructure that was removed from the painting. On the right, the cover of the “Enjoy Life on Earth Forever” booklet released in 1982 that shares a similar composition and palette to the painting. That my father, a long time Witness, also began to remove these types of objects from his work isn’t surprising. He is giving you a preview of what God will supposedly soon do Himself. I believe this practice is more a sign of conformity to Witness teaching than probably even conscious choice. Because of this I would argue that my father’s art has become not “a plea to revere the earth and live in harmony with it” as Coulson says, but rather a fantasy of what Paradise will look like when we, the heathens, are all gone.

The parallels between my sisters’ art and Witness imagery found in the Watchtower is also striking. Their art has numerous examples of labourers either engaged in farming, yard maintenance or household chores but as with the Watchtower examples, always without any modern tools. They also incorporate Witness compositions of the endless delights of Paradise in their work. Or on the other hand, they also portray people looking longingly towards Paradise from the despair of this current reality.

On the left, “Generations Caring Sharing” 2017 by Nicole Minnis-Ferguson. On the right, the opening illustration of the “You Can Live Forever in Paradise on Earth” book – released in 1982.

A person looking off in the distance, yearning for Paradise, is also a familiar motif of Minnis family and Watchtower images. On the left “Sisters and Friends” by Nicole Minnis-Ferguson 1990, and on the right a Watchtower image. With very few exceptions it is possible to insert any of my family’s paintings directly into a Witness publication without modification, as if the family has been working on a Bahamian edition of the Watchtower magazine, consciously or not, for their entire careers.

I don’t think these connections are coincidence because these are the images that my family has been consuming for decades and that my sisters and I were literally raised on.

Interestingly enough, Nicole has actually worked for years in the Watchtower art department in New York and has likely produced a few anonymous masterpieces for them — anonymous because all the work published by the Watchtower goes unattributed to enhance the illusion that it comes from divine sources.

3.

The family has come under criticism in recent years as their work has grown increasingly out of step with contemporary Bahamian art practice. In the Director’s Cut my father addresses this criticism by saying that “some people call what we do chocolate box cover art.” According to Coulson, some also describe their work as “mere decoration.”

Is Minnis family art like this though because of the demands of the marketplace or because their religion doesn’t allow them to be anything else?

As the example of my life shows, Jehovah’s Witnesses discourage freedom of thought, and anything a Witness does or creates that could be seen as being “worldly” or against Watchtower doctrine could lead to punishment.

While there’s definite market pressure to produce work that is safe for the majority of buyers, I believe fear of going against Witness rules also plays a large part in defining their art’s content. This dual pressure leaves little room for experimentation, play or growth — many of the very things that we expect out of artists but are, for the most part, absent in their work.

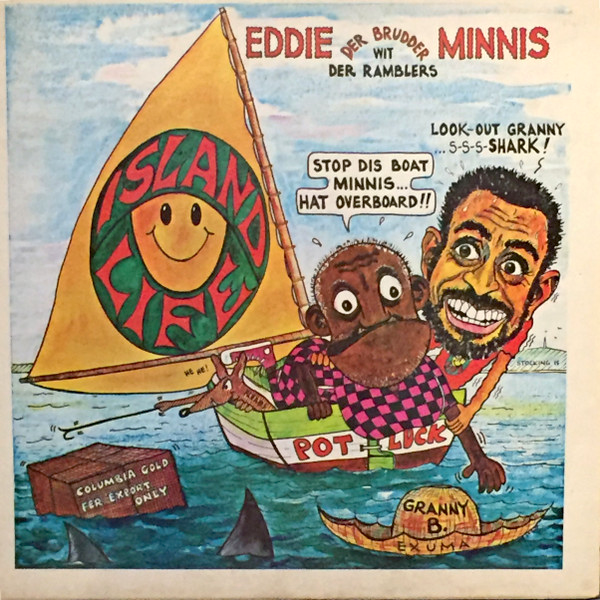

The impact of this religious pressure from the Witnesses and how this affects their art is probably best seen in the example of my father’s Pot Luck cartoons. For ten years from 1971 he was the leading commentator on Bahamian politics with his immensely popular editorial cartoons. Even though this was something he had started before he converted, his practice gradually came into conflict with evolving Witness teachings on the matter.

Witnesses discourage members from expressing or even having an opinion on politics and this stand became more hard-line in the late 1970s. I have heard a few stories about this, but they are all some version of him having to make a choice between his faith and Pot Luck. In the end, he chose to be a good Witness and abruptly ended his influential creation.

Witness rules on politics also extended to his music and he soon ended his satirical work there too.

While his albums were never fully political, songs like “People to People” — a sharp skewering of the Ministry of Tourism’s 1975 program of the same name – and “Show & Tell” – a blow-by-blow account of shenanigans surrounding the 1976 Public Disclosure Act — were political and satirical standouts, not to mention big hits. This type of material vanished from his music around the same time that he cancelled Pot Luck.

“Island Life,” released in 1979, is probably the last serious Eddie Minnis satirical album. It had songs like “Granny Flyin’” – that skewered The Bahamas’ role in the drug trade and “Nassau People” – a pointed commentary on crime. On the album cover Fleabs is seen trying to pull in a box of “Columbia Gold.” In retrospect, it appears that his cartooning helped fuel many of the sharp insights, both political and social, that he then brought to his music. Once Pot Luck ended in 1981, the music was left anchor-less, and began to drift in a more judgmental and preachy direction.

A good example of the difference between his Pot Luck era work and his more recent output is the lone new song that he recorded for his first Greatest Hits album released in 1996 entitled “Reap What You Sow.” On an album filled with political and satirical classics like ‘Nassau People’, ‘Show & Tell‘ and ‘People to People’ this new song featured lines like:

“Listen to what the Bible say / It say if you plant it / it will grow. / And you will reap what you sow. / If you don’t want to ruin your life / Remember sex was made for husband and wife.”

It wasn’t a hit.

On a certain level, of course, the song was also social commentary, but most, if not all, of the humour, compassion and most importantly, relevance, were gone.

4.

There’s a clip in “Ting an’ Ting” where I claim that my father could have done “more”, after which I receive an immediate narrative rebuke as the film cuts to Fred Sturrup saying that “To think about Eddie giving more would be selfish.”

Am I being selfish though? I understand that I have a perspective on this topic that’s not widely shared, but my point of view is deeply grounded in my own experience.

I know that being a good Witness put a cap on the art that I was able to produce. Simply put, what I created as I was leaving the religion wouldn’t have been possible if I had remained. By leaving the Witnesses I was able to explore my feelings without fear of offending an Elder or going against their theology.

What I created as I was freeing myself from the religion would not have been possible had I remained a Witness

For example, when I sent a draft of my play “The Cabinet” for my mother to read, I had forgotten that Witnesses don’t believe in an immortal soul and see any depiction of a ghost as something satanic. She was so offended by the ghost that was a central character in the play that I don’t even know if she finished reading it.

In this light, my father’s career can be best understood if we divided it in two. He began as a Bahamian trailblazer. His early years were full of national firsts like his cartooning, bold strokes like his painting on the side of the road and showed clear ambition. It seemed that he was always looking to do something new and fresh and from everything I have heard he was a carefree and fun-loving person. This joy of life could be seen in his early work and in the energy he put into the Bahamian art scene.

The second phase of his career came after he joined the Witnesses and became more and more religious, perhaps fully manifesting in 1981 with the cancellation of Pot Luck. Following the Witness mandate to be “no part of this world” there was a narrowing of his social focus and a closing of his world view. All his energy was then put into his evangelizing and in the little time that he had left he stuck to the well-worn paths he had already cleared. His palette knife technique got tighter, the music became less relevant and Pot Luck disappeared.

As for my sisters, they have been locked into their styles and subject matter since the beginning of their careers and their art has always been more about making a living than self-expression.

So what I’m thinking about when I say that my father, and by extension my sisters, could do “more” is an admittedly imaginary world where they are free from their Witness lockdown.

If they were just freed from the enormous time commitments of the Witness lifestyle they could create more art — quantity, but I believe that if they also dropped the Witness outlook on the world, their art would be of a far different quality.

You can call me selfish for having this dream, but this is the Minnis art I wish I could see.

5.

It’s impossible to calculate the total price my family has paid to be good Jehovah’s Witnesses. I know the cost to me and my life has been astronomically high.

It’s an interesting yet frustrating thought experiment to imagine what we as a family could have been had we not been Witnesses or at least, not taken it so seriously.

Despite their choices, my father is still recognized as a Bahamian icon and legend and my sisters have cemented their place in the local arts; such is the power of their talent. Perhaps in the end, to a young nation in need of artists and heroes, it doesn’t matter. We have what we have and we should be grateful.

On the other hand, I am always left with the sorrow of what could have been and what we will never get to witness.

Coming up next: Follow me as I uncover what happens when silence, religion, and respectability politics combine. Bust out your tinfoil hats for a full-blown "Bahamian Conspiracy Theory." -

Ventilate

Originally published in Yinna volume 2.

Windows in my head

fly open for the first time.

My soul staggers back

the effort overwhelming

strenuous.

Fatigued from years of conflict with

plaque covered panes.

Yellow, hard and gritsy

like teeth.

Now cleaned away.

Look at the view!

My soul soaks up the sight

Takes down drab drapes

confining curtains

to throw away and burn.

Blocked the sun far too long.

Breeze blows clear through

Corner cobwebs come loose

papers on the desk get unglued as

un-filed forms fall on the floor

agitating the dust bunnies

who know their multiplying days are done.

Resident musty funk fights fiercely with

this foreign freshness.

New wind kicks ass.

Unwelcome stale air

gets pushed out

back through my ears.

Phone rings insistent. Memory on line two.

Call back. Better yet;

leave a message at the tone.

Note to self:

New number needed.

Soul breathes in

deep.

Sun shining through windows

changes everything.

New in sight.

Fresh out look.

Office redecoration

top priority. -

Change of Plan

Caterpillars ugly but they die pretty.

God know why he make them so.

He told me the reason.

I forget what he said.

I love with most of my heart

God says always keep a little for yourself.

Now I know why.

Seen my tombstone.

Ones with the rest of my heart showed me.

Real nice of them.

I want to postpone the funeral

to count my blessings.

Can’t wait they say

Program done printed.

Killer obituary.

Family flying in to pay respects.

Meta-morph-a-what-ever.

Caterpillars can, so why can’t I?

Ask God. It ain’t my time.

Rebirth resembles Death.

Or precedes it.

Can't do one without the other.

Reconnect to life to live again.

Reset the breaker,

plug in the stove,

make some tea.

Get in the coffin they say.

We gone eulogize you.

Talk about how lousy you was

Why we glad you gone.

How we miss you already.

You was a good man still

Now you gone burn in heaven.

Straight jacket too damn tight.

Expectations strangling.

Break free.

Just like drowning.

Forget which way is up.

Yet. I always know

Come up for air.

Breathe!

Feeling free and falling relentlessly.

Giddy from the motion of standing still.

Memories swirl and dance on the horizon,

Turn into smoke.

Sail away into the distance

over the edge of the earth.

The dirty cocoon drops.

You changed they tell me.

If you better now, how come I can’t see it.

Let the wings dry, jackass.

Flying ain’t easy.

Those who stay on the ground always think it is.

They imagine you don’t have a care in the world.

God know that’s a lie.

Big ugly lie.

Casket still there.

Gone use it someday.

Just not now.

Got too much flying to do. -

3: My life as a Ghost

The hardest thing in life to learn is which bridge to cross and which to burn.

David Russell

The thing I remember most about leaving the Jehovah’s Witnesses was how much time it felt that I had.

By removing all of their events, readings and busy-ness from my schedule it was as if I had uncovered a whole other life. When my dad – Eddie Minnis – and my sisters Nicole and Shan say in the “Ting an’ Ting” documentary that they spend most of their time in the Witnessing work, they’re not joking. Being an active Jehovah’s Witness is like having a full-time job on top of your full-time job. And one where the boss expects you to put in more and more overtime.

With all of that time available to me I threw myself into my studies at the College of the Bahamas. This is the period I was referring to in the documentary when I said that I “locked myself in a room and just painted.” The room in question was the second floor of COB’s S-Block where I was doing an associate’s degree in Art with an unofficial minor in English with classmates and colleagues like Jace McKinney, Lavar Munroe and Jackson Petit.

I was twenty-five and I was a newborn. Everything was fresh, foreign and strange. I got to celebrate my birthday and Christmas for the first time. Went to Junkanoo. Dated non-Witness women. I joined Track Road Theatre where amongst other lessons I learned to curse.

Celebrating my first Christmas in 2003 at the ripe old age of twenty-six. What I was learning though were things that most people had learned when they were in their early teens or never had to learn at all.

Reminders of my past life still haunted me. Nassau is a small place and I kept running into former friends, or as I was trained to call them, “brothers”, who would no longer look me in the eye or speak to me. Each encounter was like sandpaper on my soul.

Not only was I now disfellowshipped but because I had stopped believing and could back up my non-belief, I had earned another label: “Apostate”. For Witnesses, apostates are described as stand-ins for the Devil himself. While they practice shunning of former members, they practically run away from apostates. It was like they all owed me money.

1.

When my doubts about Witness teachings really began to show, my family staged an intervention. My parents invited me to Eleuthera for a few days to talk about things. They did everything but burn sage in the house. They sympathized, shared some of their own nagging doubts. My father even said that he had come to similar conclusions as I had about certain Witness doctrines.

They sent me to visit a family friend in Rock Sound who was also an Elder. They hoped that maybe he could get through to me. After a day of trying he threw up his hands and said that this was my artistic nature coming out and there was nothing he could do.

At this point it was obvious that I wasn’t long for the faith. The Witnesses wouldn’t, couldn’t just let me be. The Elders would come as inevitably as the Terminators and I would be thrown out. This was when my sisters cried over me, when my family begged me to shut my mouth and just fade.

It felt like I was attending my own funeral.

The Witnesses wouldn’t, couldn’t just let me be. The Elders would come as inevitably as the Terminators and I would be thrown out.

As expected and as the Watchtower instructed, once the inevitable announcement came for me, it was as if I was suddenly dead to them.

My sisters have seen me walking on the road in Nassau and pressed gas.

My parents stopped supporting me through my studies at COB and left my maternal Aunt and Uncle to pick up that financial slack.

None of them came to see my play “The Cabinet” when it was on at the Dundas or the old Shirley Street Theatre.

None of them came to my wedding.

None of them visited when any of my three children were born.

2.

While my sisters have essentially cut me off, to say that my parents don’t talk to me is not entirely true. It’s a bit more complicated than that.

What communication we do have is strained. For example, I call my parents every year on their wedding anniversary, it’s one of the few things Witnesses are allowed to commemorate, and sometimes that has been our only contact for the year. If there is a life event, like an accident or a hospital visit, I get a call from them to let me know about it. If I start calling too frequently then I am told to stop.

When we do talk, the conversation is cordial, as if there is nothing wrong – as long as we stick to generalities and avoid any touchy subjects.

My three children – their only grandchildren – are a bone of contention. My parents have told me that the reason they don’t have a relationship with them is because of me. Apparently I need to let them all interact without my apostate self getting in the way. In other words, I need to give them my kids then leave the room.

Now, I know the Witness playbook too well to fall for that one. I don’t want my kids to get even a whiff of indoctrination so my response to that suggestion has always been a definitive “hell, no.”

A few years ago my mother accepted my terms and started calling the kids with me in earshot. While my father hardly ever joined in, she called about every week for almost a year and then just suddenly stopped. We later learned that since I was involved, even in such a limited role, Witness guilt had gotten the better of her. She didn’t feel that she was being faithful to Jehovah.

3.

In August of 2024 I brought my tribe with me to visit Nassau and Eleuthera. I wanted my then nine and six year old girls to get a chance to see their roots since they were now old enough to remember things. I was beyond shocked when my parents – and my sisters – said that they wanted to meet us. I was even more surprised when they showed up in broad daylight and came inside.

These were all unprecedented actions. For Nicole that was the absolute first time that she had ever seen or talked to my wife or any of my children and for Shan it wasn’t that much better.

The whole thing was as awkward as you could imagine.

I asked them if there was some Witness rule change that would allow them to meet and visit with us and with me, an apostate. They didn’t answer. I pressed further and my father said that they had made an “exception”.

The brief and awkward reunion, August 2024 in Nassau. I refused to allow a big ‘happy’ group shot due to my skepticism. Photo 1 – left to right: Kai, Ward, Leena, Sheema and Zuri. Photo 2 – left to right: Nicole, Eddie, Sherry and Shan. It took me a while but I now think I know what that “exception” was all about. There is this Witness bylaw that they call “Theocratic Warfare.” It allows them to lie, deceive and bend the rules just a bit, or even talk to an apostate, if doing so would make their religion look better to outsiders.

The business they were likely after was removing a title card from “Ting an’ Ting” that said my kids don’t know their aunts or grandparents. So having met my children, ever so briefly, the text was removed as being inaccurate and then things promptly went back to being the way they were before. Silence from the sisters and my father, and the every-so-often calls from my mother.

I was suckered.

While the few “exceptions” exhaust and annoy me, they do seem to confuse my extended non-Witness family. Mission accomplished, I guess.

It’s led some of them to believe that maybe the thing blocking a reunion with my parents and sisters is me. While this might be true now, this was not always the case. I had long hoped that my family would find in themselves the power to break free from the Watchtower’s grasp and join me on the outside.

This hope also goes in the other direction. In the Director’s Cut my sister Shan says that “the door is not shut [for me].” She continued, “Where there is life there is always hope and we’re always hoping for the best.” The “best” that she is referring to, and the only way that I can be a part of the family again, is for me to repent for the crime of having thoughts of my own and return to the Witnesses.

For over two decades then my family and I have stood on opposite sides of a ravine. Each side hoping for the other to switch.

I now believe that our separate and opposite hopes are delusional.

It’s time we all moved on.

Facebook conversation on this post

Coming up next: "House Arrest and Daydreams" — I count the hidden cost of life under Jehovah’s Witness authority... and the price my family continues to pay. -

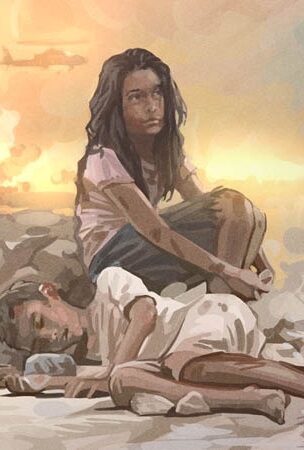

Chasm

Chasm. 2003 Acrylic on Canvas. In the collection of Katina Mosko.