Tragedy is the difference between what is and what could have been.

Abba Eban

“God had to be first – no compromise, family had to be second.”

This is how my father describes his life’s priorities in the “Ting an’ Ting” documentary. Now, this is not an unusual stand in a religious society like the Bahamas, but what does it mean to be a Jehovah’s Witness with “no compromises”? When the main thing in your life is devotion to a cult what follows from that?

This is not the position of every Jehovah’s Witness, mind you. There are Witnesses who maintain relationships with disfellowshipped children and grandchildren. There are those who just live their lives; knock on some doors every other week and do just enough to maintain their standing. But these aren’t the role models, they aren’t the people who are celebrated at Witness conventions.

Witnesses can’t force all of their members to have the same level of fanaticism. Those that don’t display the right amount of zeal forfeit any hope of advancement. For example, you can’t be an Elder if your house isn’t kept in order. Until I “took a tangent,” to borrow his phrase, my father’s house was very much in order.

1.

To understand the Minnis family is to know that because they want to be good Jehovah’s Witnesses they have placed themselves under house arrest. It’s hard enough to be a regular cult member but to be a good one requires so much more.

This means that many of the decisions in their lives are made for them. From the very basic and trivial, like how they spend their time, to larger concerns, like whether or not to go to University, to have children or whether or not they can have a blood transfusion. You can see the impact of this core decision expressed over and over again in almost every aspect of their lives.

Because they want to be good Jehovah’s Witnesses they have placed themselves under house arrest.

Take higher education for example. When I finished high school in Eleuthera I didn’t even bother to apply to a college. I wanted to put Jehovah first just like everyone else before me had done and therefore didn’t see the point. I was going to be a “Pioneer” minister. I didn’t even know how I was going to make a living. Paint, I guess?

The Watchtower does not flat out say “Thou must not go to University.” What it does instead is call it a “personal decision” then not-so-gently tell you what to do anyway. Witness literature portrays Colleges and Universities as the home of Satanic philosophy. Since the end-of-all-things is so near, their argument goes, do you want to spend the short time left getting a degree in Satan’s home or earn God’s favour by knocking on doors? The “decision” is left up to the individual but if they want to be a good Witness the choice is clear.

If a Witness does decide to go, as I later did, they are judged for that choice and are labelled as not being ‘spiritual’ enough. While I was a member I couldn’t shake the guilt I felt for going to COB. Of course, my later turn away from the religion was chalked up as proof that Watchtower was right all along.

My sisters had the same mindset when they graduated high school. They both excelled academically, especially Shan, who got a remarkable eight A’s in her GCE O levels. Despite the obvious talent, they did not pursue any form of higher education. If memory serves, Shan actually applied and got accepted to numerous Universities, only to turn them all down.

The end of the world was apparently so near when they finished high school in the late 80s that there was no time to get degrees. They were applauded at the Kingdom Hall for making the best choice by giving Jehovah their youth.

Fast forward to now, nearly forty years later, the imminent nearness of Armageddon was still being used to scare others into the same dead-end choices up until very recently. On August 22nd the Witnesses suddenly reversed their decades long stance on ‘additional education’ – and have now made it ok for their members to pursue it if they so choose.

In making this radical U-turn, they didn’t apologize for their failed predictions or for the consequences their policies have had on millions of people. They won’t be made accountable for all the potential that they have wasted. In the end, it’s people like Nicole and Shan who are left holding the bag.

2.

Witness teachings like the Paradise Earth are deeply embedded in the family’s art. Paradise is the hope that the majority of members believe in and cling to; that after Armageddon they will get to live forever on Earth without sickness and death.

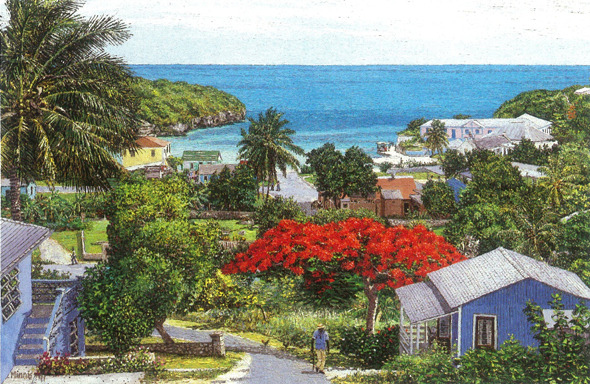

For example, when my father began his art practice, his landscape paintings would capture the complete view of a scene almost like an historian. However over time, as Amanda Coulson observes, he “began to deliberately excise objects of human intervention – cars, telephone poles, even the people themselves.”

This practice of removing traces of modern life from his paintings actually mirrors Witness images of paradise that also don’t include modern objects. Images in the Watchtower that do include things like telephone poles and street lights are horrific scenes from their imagined Armageddon.

“Objects of human intervention”, are therefore used as a kind of visual shorthand to show an image’s place in the Witness’ end-of-the-world timeline. Apparently, there will be no street lights in Paradise.

That my father, a long time Witness, also began to remove these types of objects from his work isn’t surprising. He is giving you a preview of what God will supposedly soon do Himself. I believe this practice is more a sign of conformity to Witness teaching than probably even conscious choice. Because of this I would argue that my father’s art has become not “a plea to revere the earth and live in harmony with it” as Coulson says, but rather a fantasy of what Paradise will look like when we, the heathens, are all gone.

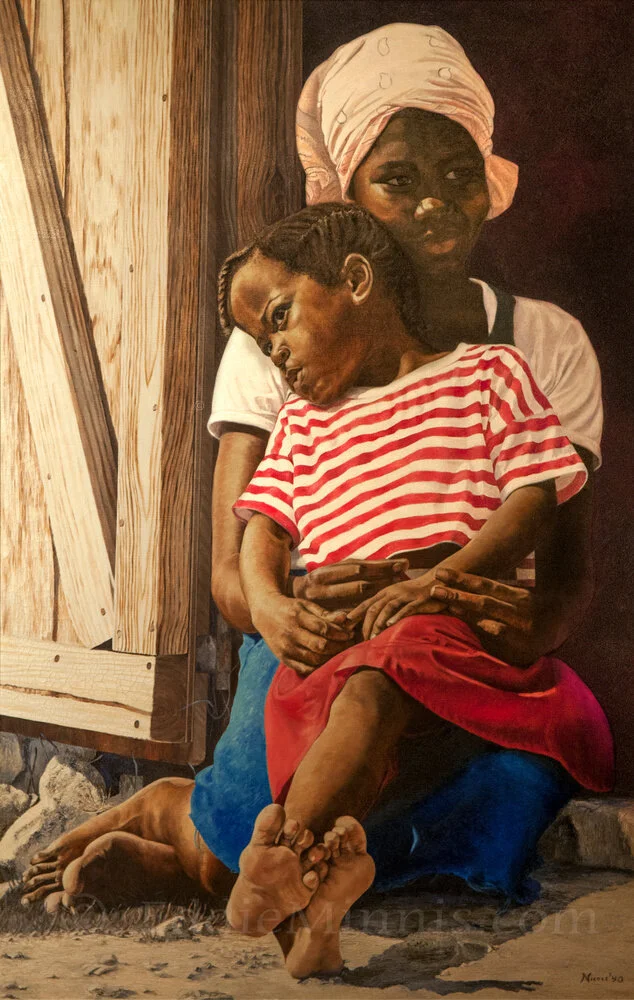

The parallels between my sisters’ art and Witness imagery found in the Watchtower is also striking. Their art has numerous examples of labourers either engaged in farming, yard maintenance or household chores but as with the Watchtower examples, always without any modern tools. They also incorporate Witness compositions of the endless delights of Paradise in their work. Or on the other hand, they also portray people looking longingly towards Paradise from the despair of this current reality.

With very few exceptions it is possible to insert any of my family’s paintings directly into a Witness publication without modification, as if the family has been working on a Bahamian edition of the Watchtower magazine, consciously or not, for their entire careers.

I don’t think these connections are coincidence because these are the images that my family has been consuming for decades and that my sisters and I were literally raised on.

Interestingly enough, Nicole has actually worked for years in the Watchtower art department in New York and has likely produced a few anonymous masterpieces for them — anonymous because all the work published by the Watchtower goes unattributed to enhance the illusion that it comes from divine sources.

3.

The family has come under criticism in recent years as their work has grown increasingly out of step with contemporary Bahamian art practice. In the Director’s Cut my father addresses this criticism by saying that “some people call what we do chocolate box cover art.” According to Coulson, some also describe their work as “mere decoration.”

Is Minnis family art like this though because of the demands of the marketplace or because their religion doesn’t allow them to be anything else?

As the example of my life shows, Jehovah’s Witnesses discourage freedom of thought, and anything a Witness does or creates that could be seen as being “worldly” or against Watchtower doctrine could lead to punishment.

While there’s definite market pressure to produce work that is safe for the majority of buyers, I believe fear of going against Witness rules also plays a large part in defining their art’s content. This dual pressure leaves little room for experimentation, play or growth — many of the very things that we expect out of artists but are, for the most part, absent in their work.

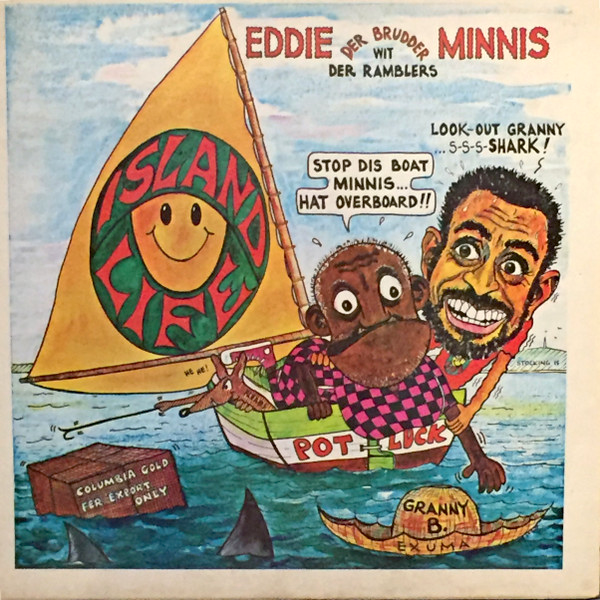

The impact of this religious pressure from the Witnesses and how this affects their art is probably best seen in the example of my father’s Pot Luck cartoons. For ten years from 1971 he was the leading commentator on Bahamian politics with his immensely popular editorial cartoons. Even though this was something he had started before he converted, his practice gradually came into conflict with evolving Witness teachings on the matter.

Witnesses discourage members from expressing or even having an opinion on politics and this stand became more hard-line in the late 1970s. I have heard a few stories about this, but they are all some version of him having to make a choice between his faith and Pot Luck. In the end, he chose to be a good Witness and abruptly ended his influential creation.

Witness rules on politics also extended to his music and he soon ended his satirical work there too.

While his albums were never fully political, songs like “People to People” — a sharp skewering of the Ministry of Tourism’s 1975 program of the same name – and “Show & Tell” – a blow-by-blow account of shenanigans surrounding the 1976 Public Disclosure Act — were political and satirical standouts, not to mention big hits. This type of material vanished from his music around the same time that he cancelled Pot Luck.

In retrospect, it appears that his cartooning helped fuel many of the sharp insights, both political and social, that he then brought to his music. Once Pot Luck ended in 1981, the music was left anchor-less, and began to drift in a more judgmental and preachy direction.

A good example of the difference between his Pot Luck era work and his more recent output is the lone new song that he recorded for his first Greatest Hits album released in 1996 entitled “Reap What You Sow.” On an album filled with political and satirical classics like ‘Nassau People’, ‘Show & Tell‘ and ‘People to People’ this new song featured lines like:

“Listen to what the Bible say / It say if you plant it / it will grow. / And you will reap what you sow. / If you don’t want to ruin your life / Remember sex was made for husband and wife.”

It wasn’t a hit.

On a certain level, of course, the song was also social commentary, but most, if not all, of the humour, compassion and most importantly, relevance, were gone.

4.

There’s a clip in “Ting an’ Ting” where I claim that my father could have done “more”, after which I receive an immediate narrative rebuke as the film cuts to Fred Sturrup saying that “To think about Eddie giving more would be selfish.”

Am I being selfish though? I understand that I have a perspective on this topic that’s not widely shared, but my point of view is deeply grounded in my own experience.

I know that being a good Witness put a cap on the art that I was able to produce. Simply put, what I created as I was leaving the religion wouldn’t have been possible if I had remained. By leaving the Witnesses I was able to explore my feelings without fear of offending an Elder or going against their theology.

What I created as I was freeing myself from the religion would not have been possible had I remained a Witness

For example, when I sent a draft of my play “The Cabinet” for my mother to read, I had forgotten that Witnesses don’t believe in an immortal soul and see any depiction of a ghost as something satanic. She was so offended by the ghost that was a central character in the play that I don’t even know if she finished reading it.

In this light, my father’s career can be best understood if we divided it in two. He began as a Bahamian trailblazer. His early years were full of national firsts like his cartooning, bold strokes like his painting on the side of the road and showed clear ambition. It seemed that he was always looking to do something new and fresh and from everything I have heard he was a carefree and fun-loving person. This joy of life could be seen in his early work and in the energy he put into the Bahamian art scene.

The second phase of his career came after he joined the Witnesses and became more and more religious, perhaps fully manifesting in 1981 with the cancellation of Pot Luck. Following the Witness mandate to be “no part of this world” there was a narrowing of his social focus and a closing of his world view. All his energy was then put into his evangelizing and in the little time that he had left he stuck to the well-worn paths he had already cleared. His palette knife technique got tighter, the music became less relevant and Pot Luck disappeared.

As for my sisters, they have been locked into their styles and subject matter since the beginning of their careers and their art has always been more about making a living than self-expression.

So what I’m thinking about when I say that my father, and by extension my sisters, could do “more” is an admittedly imaginary world where they are free from their Witness lockdown.

If they were just freed from the enormous time commitments of the Witness lifestyle they could create more art — quantity, but I believe that if they also dropped the Witness outlook on the world, their art would be of a far different quality.

You can call me selfish for having this dream, but this is the Minnis art I wish I could see.

5.

It’s impossible to calculate the total price my family has paid to be good Jehovah’s Witnesses. I know the cost to me and my life has been astronomically high.

It’s an interesting yet frustrating thought experiment to imagine what we as a family could have been had we not been Witnesses or at least, not taken it so seriously.

Despite their choices, my father is still recognized as a Bahamian icon and legend and my sisters have cemented their place in the local arts; such is the power of their talent. Perhaps in the end, to a young nation in need of artists and heroes, it doesn’t matter. We have what we have and we should be grateful.

On the other hand, I am always left with the sorrow of what could have been and what we will never get to witness.

Coming up next: Follow me as I uncover what happens when silence, religion, and respectability politics combine. Bust out your tinfoil hats for a full-blown "Bahamian Conspiracy Theory."

Leave a Reply